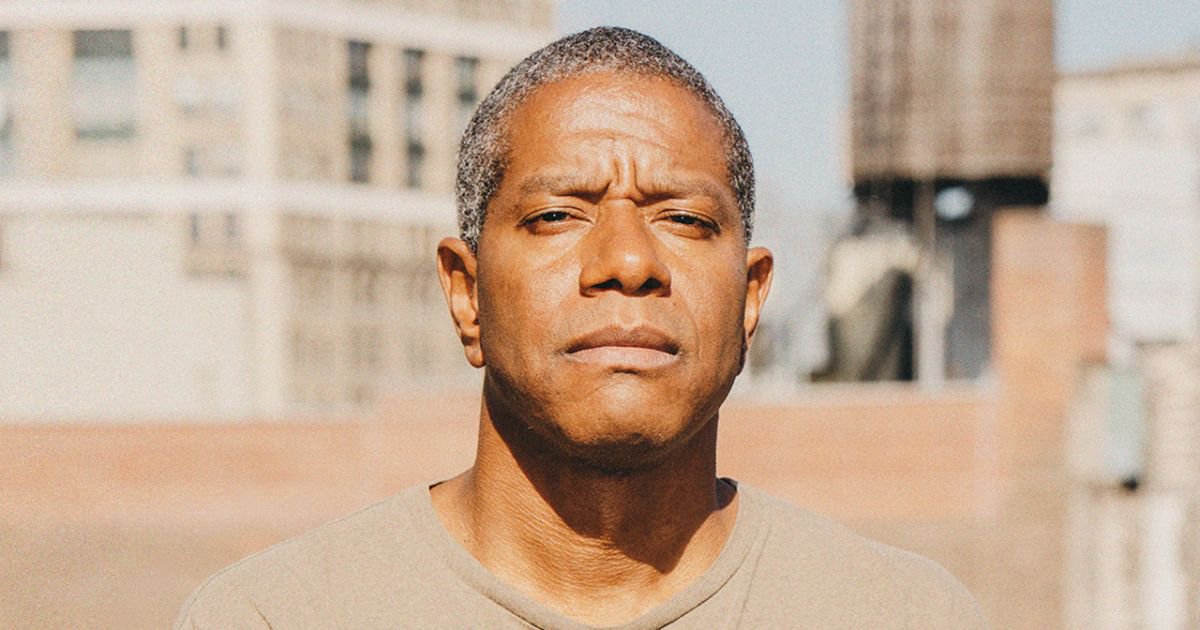

“Paul Beatty Is Creating Space for Writers of Color”

By James Yeh, originally published in Playboy Magazine (2016)

Photo by Ryan Lowry

“For me it all starts with the language,” says the 54-year-old novelist (who was also the first-ever Grand Poetry Slam champion in 1990). “That’s where all the fucking latticework is for me.” Indeed, the thrill of The Sellout lies not only in Beatty’s delirious conceit, but in his virtuoso riffs, which take bull’s-eye aim at race, class, pop culture and propriety in our supposedly postracial, allegedly hyper-PC America.

“The book is a lot about dissonance,” Beatty says, “about what you can do and what you can say.” And, boy, does he ever say it, whether he’s cataloging various absurd African American stereotypes—“the dual-threat quarterbacks,” “the weekend weather forecasters”—or coining terms such as “Afro-agrarian,” “Allah ak-open bar” and “languid bojangle.”

“I get nervous when things don’t make people nervous,” Beatty admits in his laidback, California way. “I feel like a lot of writers of color feel like there are just certain directions that they have to take: what your point of view should be, who can do what, how positive it has to be. Somebody’s always going to tell you what it means to be a black writer, what responsibilities you have. [So] just trying to create some space is really important to me.”

And that’s exactly what Beatty does, obliterating the boundaries of what is funny, what is profane and what is just so sad and unfixable that we can only laugh to keep from crying—or shooting. There’s a bit of truth in every good joke, and perhaps in that truth we are able, after the laughs subside, to better see the world and ourselves in it.

Originally published in the October 2016 issue of Playboy Magazine.